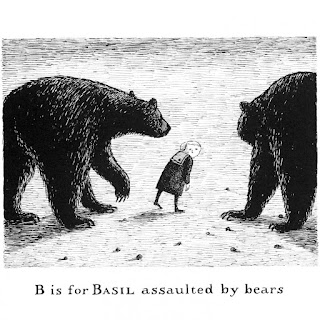

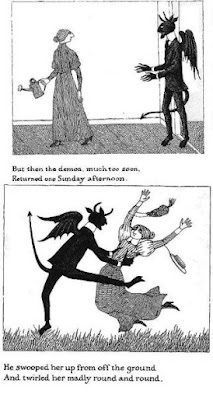

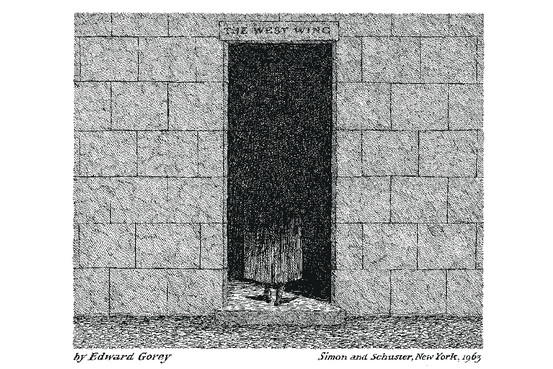

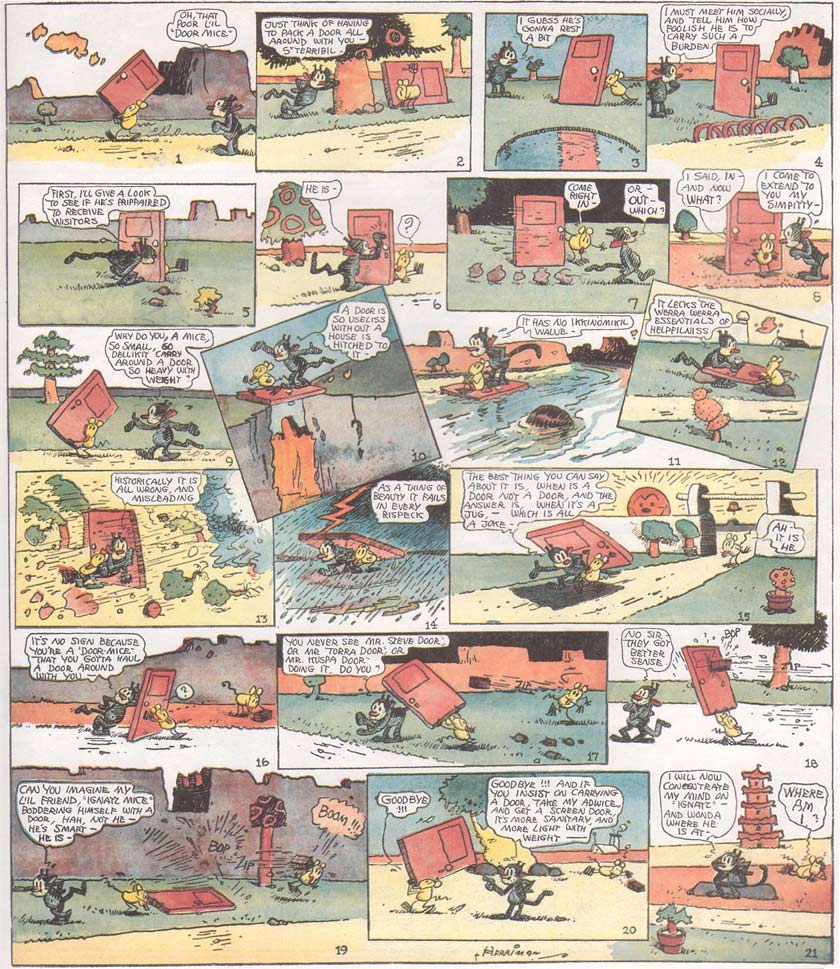

I first encountered Edward Gorey as an illustrator; he did the drawings for a peculiar little 1961 book by Paul Behn (who, by the way, went on to write the screenplays for two Planet of the Apes sequels, in large part because of his concerns over nuclear proliferation) I bought as a kid, Quake, Quake, Quake, a collection of Cold War nursery rhymes that mimicked established rhymes and poems, including (which I did not know at the time) Tennyson's Break, Break, Break. I liked the book, and loved the illustrations. So I started looking for Gorey, and discovered he was a prolific writer who popped up everywhere, including, in the '70s, National Lampoon magazine. But he also designed the sets for a '70s production of Dracula and continued to show up in odd corners of pop culture, including the animated opening of PBS's Mystery! series.

(Gorey, early 1970s)

But it was his own slim volumes, shaped like children's books but not really, that most attracted me. I'd read Jane Eyre when I was a little kid, and the woodcuts of the famous Random House edition of that book (along with Wuthering Heights) addicted me to finely detailed, crosshatched drawing. And boy did Gorey deliver—but with the added bonus of creating a sideways universe of Victorian quiet, Edwardian delicacy—and all the bottomless strangeness that lies lurking back there in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

But let's leave it there so you can look at these here: