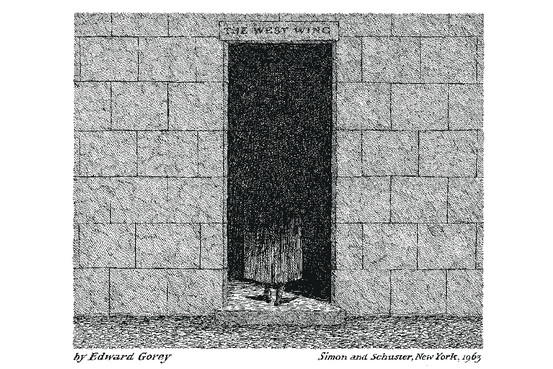

mise en abyme, or the Droste Effect

Published between 1759 and 1767, Tristram Shandy remains a novel I'm certain was written by a time-traveller who went back to the later 18th century just to fuck with people. Here's the first chapter, in its entirety:

I wish either my father or my mother, or indeed both of them, as they were in duty both equally bound to it, had minded what they were about when they begot me; had they duly consider’d how much depended upon what they were then doing;—that not only the production of a rational Being was concerned in it, but that possibly the happy formation and temperature of his body, perhaps his genius and the very cast of his mind;—and, for aught they knew to the contrary, even the fortunes of his whole house might take their turn from the humours and dispositions which were then uppermost;—Had they duly weighed and considered all this, and proceeded accordingly,—I am verily persuaded I should have made a quite different figure in the world, from that in which the reader is likely to see me.—Believe me, good folks, this is not so inconsiderable a thing as many of you may think it;—you have all, I dare say, heard of the animal spirits, as how they are transfused from father to son, &c. &c.—and a great deal to that purpose:—Well, you may take my word, that nine parts in ten of a man’s sense or his nonsense, his successes and miscarriages in this world depend upon their motions and activity, and the different tracks and trains you put them into, so that when they are once set a-going, whether right or wrong, ’tis not a half-penny matter,—away they go cluttering like hey-go mad; and by treading the same steps over and over again, they presently make a road of it, as plain and as smooth as a garden-walk, which, when they are once used to, the Devil himself sometimes shall not be able to drive them off it.

Pray my Dear, quoth my mother, have you not forgot to wind up the clock?—Good G—! cried my father, making an exclamation, but taking care to moderate his voice at the same time,——Did ever woman, since the creation of the world, interrupt a man with such a silly question? Pray, what was your father saying?————Nothing.

The hero announces on page one that his character and life have been irrevocably altered because his father stopped during the hero's conception to wind a clock. It is a conception conception that is at once funny and tragic (in a funny way), an early announcement that the smallest thing, often beyond our control, makes all the difference.

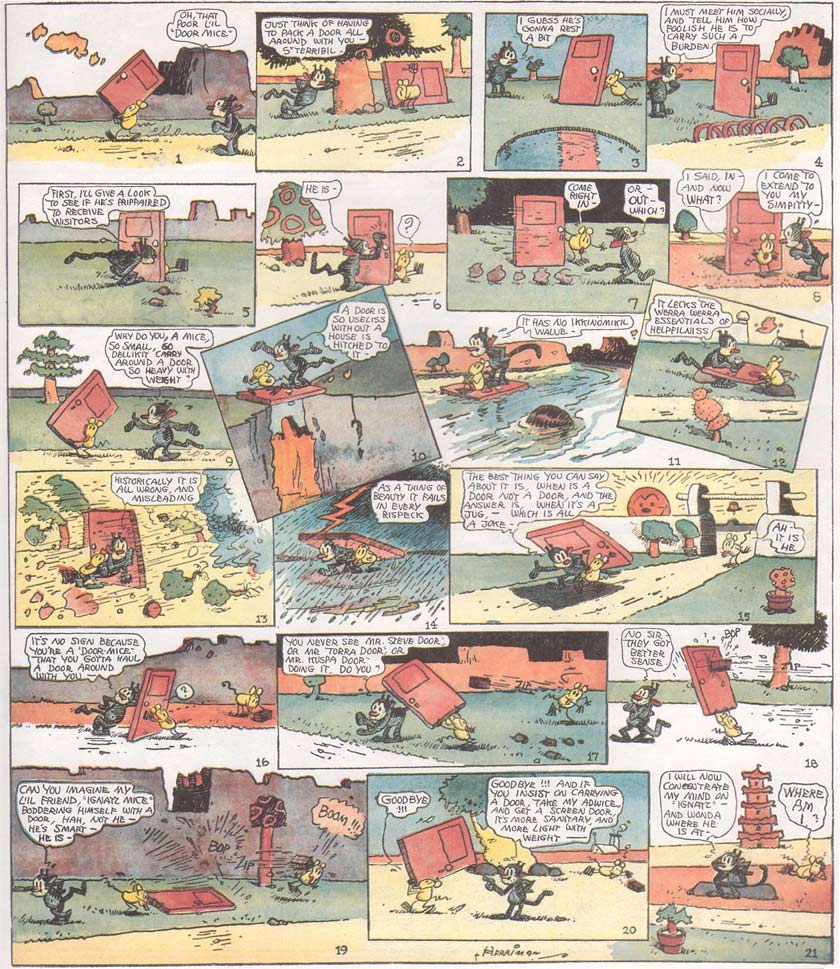

But that is not where the novel rests. No, Tristram tries heroically to live—well, at least to start the novel. And that is what I, a fellow weirdo, love about this book: the constant digressions, sidetracks, backtracks, and tangents. I talk that way, and I like to write that way. Well, I did read this as an undergrad, and it seeped into my already-teeming-with-flotsam-and-effluvia brain, and over the decades has had as profound effect on my path as an unwound clock.

If you can bear the constant irony and meta-ness, if you love hearing a story that the storyteller constantly interrupts with lengthy addenda and other stories (and as I write that, it sounds like torture), then this is the tale for you. Just don't get too close to the mise en abyme.

(btw there's a pretty good film, A Cock and Bull Story (2006), somehow wrenched out of the heart of this book. A movie version is being made of the novel, and like the novel, it's a movie about trying (and essentially failing) to make a movie.